Introduction to the Permanent Forestry Category

The “Permanent Forestry” category became available in 2023 and was designed for forest that is not intended to be harvested, such as native forest. The category can also be used for exotic forestry blocks that may not be profitable to harvest because they are too small, too remote, or untended (not pruned or thinned). To qualify for the permanent category, forest must be “post-1989” forest (planted on land that was not forested on 31 December 1989). Forest owners who register forest in the permanent category warrant that they will not clearfell the forest for at least 50 years from the date of registration. In return, they can claim carbon credits up to age 50 and potentially beyond.

At first glance, the permanent category seems attractive for carbon forestry or 'carbon farming', offering superior returns to many other land uses, including conventional production forestry. However, closer examination reveals it as a proposition requiring careful consideration. In this article, we will examine the potential risks and rewards as well as various other aspects of the permanent forestry category.

Contact the PF Olsen ETS team today

What are the benefits of registering forest in the permanent category?

- The permanent category is now the only way of accessing stock change carbon accounting for forests entering the ETS. Under stock change carbon accounting, trees can earn carbon credits up to age 50 and potentially beyond. By contrast, under the averaging accounting system, trees can only earn carbon credits up to their average age, which is 16 years in the case of radiata pine.

- Barring any major adverse natural events and subject to carbon market fluctuations, carbon forests registered in the permanent category can generate attractive returns for the forest owner.

What are the risks associated with the permanent category?

- Forest owner is going “all in” on carbon, rather than spreading risk between carbon and timber.

- Difficult to predict with any accuracy how carbon prices will develop in the long term.

- Difficult to predict with any accuracy how timber prices and harvesting technologies will develop in the long term. The balance of attractiveness of carbon vs timber could change in the course of 50 years.

- High likelihood of adverse impact on land value.

- Significant probability of natural event (e.g. fire, disease, windthrow) occurring during 50-year timeframe that will create costs and reduce carbon income.

- Significant probability of new regulations and restrictions, which could increase overhead costs or otherwise change the economics of forests in the permanent category.

What sort of return can be expected from a forest registered in the permanent category?

The return will depend on the price of carbon, the applicable carbon table, and whether the forest suffers any adverse events that compromise its “carbon credit earning” potential. To provide a fair and reasonable idea of a possible return from a forest registered in the permanent category, we must make some fair and reasonable assumptions.

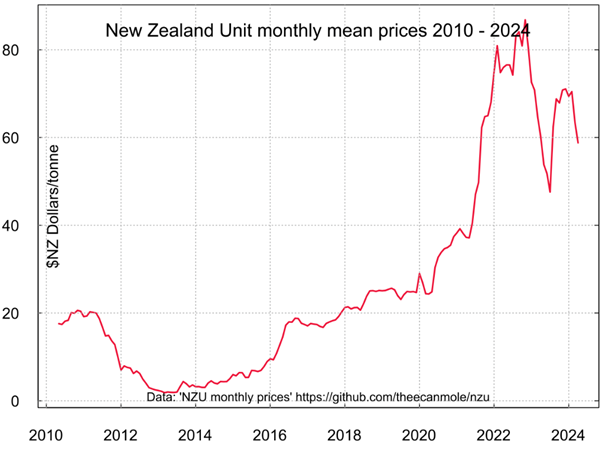

The price of carbon is set by a combination of supply and demand in New Zealand’s secondary carbon market and the quarterly government carbon auctions, which release additional carbon credits into the market. Since the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme was introduced in 2008, the price of carbon has undergone enormous fluctuations, as shown in the graph below.

Source: Wikipedia

By far the most important factor affecting the carbon price to date has been government policy – both implemented and contemplated. Government policy is difficult to predict, especially over long timeframes. For the purposes of this analysis, we will assume a carbon price that stays fixed at $40.

Carbon tables determine how many carbon credits a forest is entitled to. The applicable carbon table depends on the size and location of the ETS-registered forest. Pinus radiata forests below 100 hectares in size use the generic government look-up carbon table for their region, whereas Pinus radiata forests over 100 hectares in size get their own custom carbon table. Custom carbon tables are usually, though not necessarily always, better than the generic government carbon tables. For the purposes of this analysis, we will use the generic government carbon table for Pinus radiata in the Hawkes Bay/Southern North Island region.

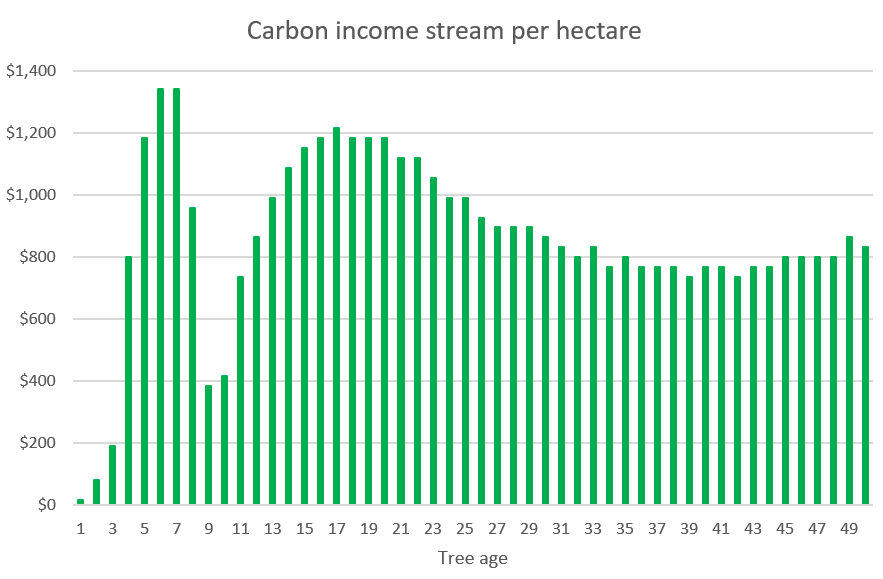

Our final assumption is that, due to natural adverse events, such as fire or windthrow, our forest only receives 80% of its maximum possible carbon credit entitlement over the 50-year period. All of these assumptions together yield the per-hectare carbon credit income stream illustrated in the figure below. It is important to note at this point that there are also regular costs associated with being an ETS participant, which are not reflected in the figure.

Contact the PF Olsen ETS team to learn more about the potential costs and returns of ETS participation.

What happens if the forest is clearfelled during the 50-year “warranty period”?

The forest owner will face substantial penalties as well as having to return all of the carbon credits they received up to the clearfell date for the clearfelled area.

What happens if a permanent forest is destroyed by fire or other natural events during the 50-year period?

ETS participants must replant the affected area within four years of the clearance event. They also need to choose between paying back units to account for the decrease in stored carbon or lodging a Temporary Adverse Event Suspension (TAES) application. If approved, the TAES exempts the participant from having to pay back credits. Instead, the affected area will pause earning carbon credits until the replanted trees have reached the carbon stock of the original trees when these were cleared by the natural event.

What happens when the 50 years are up?

The forest owner can opt to harvest the trees and deregister from the ETS, though they would have to return all the carbon credits they received. Alternatively, they could extend by another 25 years. A third option is to move the forest to averaging accounting, in which case the forest owner would have to return all carbon credits they received after the forest reached its average age (age 16 in the case of radiata pine). This applies even if the forest was already past its average age when it was registered as in the permanent category.

Why register forest in the permanent category if carbon credits have to be paid back when the forest is eventually harvested?

There is a view that the price of carbon will decrease over the long term as New Zealand approaches carbon neutrality. However, it is impossible to know when or even if this will actually happen, which is why, in our opinion, the permanent category only makes sense for forest owners who are prepared to go “all in” on carbon and never harvest their trees.

What else should I consider before registering my forest in the permanent category?

- Is your forest in a high-risk location? High-risk locations include exposed locations (e.g. ridge tops) with a history of windthrow and locations immediately adjacent to forests under different ownership that could be harvested during the 50-year period.

- How big is your forest? Small forests (e.g. < 10 hectares) are exposed to exponentially greater risk from natural adverse events.

- What tree species have you planted or are you thinking of planting? Some tree species are more suitable for the permanent category than others. For instance, once successfully established, species such as redwoods or totara, can be expected to live for longer than many other commonly planted tree species, such as radiata pine.

- How much would it cost to clear windthrown areas to allow replanting if the windthrown trees are mature?

- Is the property your forest is planted on subject to any encumbrances that might give third parties the right to clear parts of my forest, for instance, for access / roading purposes?

My forest is registered under stock change accounting and I have no intention of harvesting it. Should I be switching it to the permanent forestry category?

We currently do not see any benefit in switching stock change forests to the permanent category. On the contrary, the permanent category comes with a number of downsides relative to the legacy stock change system:

- it imposes additional obligations on forest owners

- it exposes forest owners to additional risks

- it removes the harvest option for at least 50 years

- it is highly likely to adversely impact land value

What are “transition forests”?

The term “transition forests” means forests registered in the permanent forestry category that are initially established in fast growing exotic tree species and then gradually replaced with native tree species over a number of decades.

Compared to most commonly planted exotic tree species, native trees are costly to establish. They also take much longer to sequester carbon. The idea behind transition forests is that fast growing exotic tree species require a much lower initial investment while providing a much higher carbon income early on. This helps the forest owner finance the gradual establishment of native trees in place of the exotic “nurse crop”.

While the idea of transition forests appeals to many, the devil, as always, is in the detail. Key issues to consider include the following:

- There are few, if any, examples of forests in New Zealand that have been fully and successfully transitioned from mature exotic to mature native tree species. Although theories about the transition process abound, there is a lack of empirical data underpinning the financial and biological feasibility of the various methods that have been proposed. The costs and timeframes associated with the transition process are therefore highly uncertain. This uncertainty is further exacerbated by the fact that the transition process will likely be very location specific.

- Native forest can and often will have a much lower carbon stock than forest comprised of fast-growing exotic tree species, such as radiata pine – at least in the first 100 years. This means that forest owners may find themselves having to surrender carbon credits as they transition their permanent exotic forest to native tree species.

- The regulator has recognized this as a potential issue and has provided advice to the Government on potential regulatory changes. Whether the Government acts in this space remains uncertain, and in the meantime, owners of registered transition forests are exposed to significant regulatory risk and uncertainty.